Used Brass Restoration Hardware Tv Easle

Why Rembrandt's The Night Lookout man is still a mystery

The Dutch master's famous painting has inspired theories that advise it led to his downfall. Fisun Güner takes a closer look.

Due west

When Rembrandt van Rijn died aged 63 in 1669, he was buried in an unmarked grave, in a plot endemic by the church. Later twenty years, as was customary for those who had died in poverty, his remains were dug up and discarded. In 1909, a memorial rock was finally fixed to the north wall of the Westerkerk, the Dutch Reformed Church building in Amsterdam where he'd been buried. You can run across it today; it'due south a copy of the one that adorns the colonnaded wall – but in a higher place the plumed helmet of one of the ceremonial pike carriers – in Rembrandt's nearly famous painting The Night Watch.

More like this:

- Did Rembrandt invent the selfie?

- Eight odd details hidden in masterpieces

- Intimate images of a bathing beauty

Rembrandt had outlived all of his children past his wife, Saskia, who had died 27 years earlier, at the superlative of his success. In fact, she died the twelvemonth The Night Watch, his great, life-sized painting of one of Amsterdam'due south civic militia companies, was finished. Titus, then just a year old, was to be the only one of the couple'south four children to survive into adulthood, the others living only days or weeks.

But by the time of his begetter'south death, Titus as well was expressionless. Eleven months earlier, aged 27, he had succumbed to a plague that was spreading through the city. For Rembrandt, information technology was the concluding devastating blow in a life marked by personal tragedy, and by the financial dubiety of his terminal two decades. The artist'south common-law wife Hendrickje Stoffels (with whom he'd had a girl who survived him into adulthood) had died six years earlier. Like his two daughters built-in to Saskia, the kid was named Cornelia.

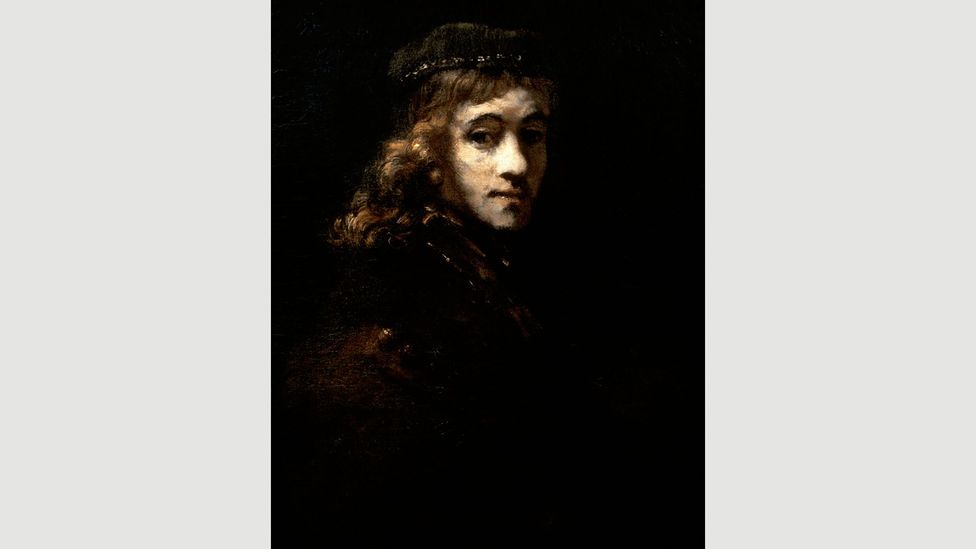

Portrait of Titus van Rijn c 1662, who succumbed to the plague, anile 27 (Credit: Louvre Museum / Getty)

It was Titus and Hendrickje, the adult female he'd initially employed as his maid, who had kept the artist financially afloat later he'd been forced to sell, in 1656, his grand house in Amsterdam's Jewish quarter (now the Rembrandt Firm Museum). His fine art collection and his exotic antiques – the latter often appearing as props in his paintings – also went to auction. Titus and Hendrickje stepped in to act jointly as his art dealers when Rembrandt was unable to trade under his own name due to prohibitive defalcation laws.

So why had the greatest artist of his age, whose death is this year being marked on its 350th anniversary with exhibitions around the earth, fallen into poverty?

Conspiracies and clues

A myth has grown around Rembrandt'southward apparent fall from favour that was, for many years, connected to The Night Watch. The painting has even inspired conspiracy theories courtesy of film director Peter Greenaway. His 2007 picture Night Watching, and follow-up documentary Rembrandt'southward J'Accuse, argue that the painting's complex iconography reveals a murder plot that leads to members of the civic militia, who information technology portrays threatening Rembrandt's life and leading to his ruin.

Films such as Alexander Korda's Rembrandt and Peter Greenaway'south Night Watching take taken considerable licence with the circumstances around the painting (Credit: Getty)

Perhaps rather less fancifully, but exercising considerable licence nonetheless, is the reaction to the painting in Alexander Korda's 1936 film Rembrandt. When The Night Watch is unveiled, with great fanfare, to members of the militia and their wives, stunned silence is quickly followed past laughter from the wives, then fury and indignation from the men. Asked by Charles Laughton's Rembrandt to tell him honestly what he thinks of the painting, the creative person'south friend and patron, Jan Vi (who, incidentally, is the subject of one of Rembrandt's greatest single portraits) doesn't agree back. "I tin come across zilch in it but shadows, darkness and confusion," he responds, with not bad animation. "You surely don't look us to take this as serious art?" Moments later, Helm Banning Cocq, who appears in the painting aslope his exquisitely attired lieutenant, both of whom are bathed in a gilt light, tells the creative person his work is a monstrosity. "Do those look like gentlemen of rank and position?" he asks, with pompous indignation.

But unless Banning Cocq's critique swiftly softened, we know that this scene couldn't have happened. Not merely do we know that the helm placed a copy of the painting in his family unit anthology, simply information technology's very probable that it was he who deputed the Dutch artist Gerrit Lundens to pigment a smaller replica, which is now in the collection of London's National Gallery (on display in the Rijksmuseum).

Rembrandt's most masterly composition, The Nighttime Spotter, 1642, uses light to lend the scene an ethereal quality (Credit: Rijksmuseum)

Painted within a few years of the original, Lundens' painting shows us what Rembrandt's masterpiece would have looked like before the sail was cutting on all sides in 1715, wherein it lost 2ft from the top, 2ft from the left, and inches from the right and bottom. Too as losing 2 figures on the left, the painting lost much of its airy architectural space, and the once off-centre figures of Banning Cocq and his second-in-command Van Ruytenburch was now aligned to the centre, arguably making the painting lose something of its sense of forward motion.

Today this would be an act of criminal vandalism, but it was then fairly common, and was done on the occasion of its removal from the company's meeting hall to Amsterdam's City Hall to fit its allocated space, where it remained on public display. In 1885 it moved to the new Rijksmuseum, where it had a gallery congenital peculiarly for information technology.

A Cocq and bull story

And then did The Night Lookout man really lead to Rembrandt's downfall? Perhaps we should expect closely at the painting, not for any clues to a conspiracy to murder, but to see how Rembrandt deviated from the norms of a sub-genre that was very pop in the new Dutch Commonwealth: the borough militia portrait, or The Guardroom Scene. And we can brand up our minds as to whether the painting might have brought displeasure to those who'd commissioned information technology.

It was certainly Rembrandt's most masterly composition to date, which, post cut, all the same measures nearly 12ft x 14ft (iii.65 x four.26m). In this richly hued, tenebrous masterpiece, where lite is used to lend the scene an ethereal quality among the commonplace bustle of move and activeness, we detect a certain strangeness, a certain unreality to the scene – even though information technology's a painting full of dissonance.

Simply every bit the Flemish artist Van Eyck loved to practice, Rembrandt painted himself hidden inside the scene (Credit: Rijksmuseum)

Here a frisky dog barks; a drummer beats his big drum, readying to proceed time with the marching guards; a male child is seen at the furthest edge to the left, looking back every bit he runs off carrying a gunpowder horn; a guard tinkers with the muzzle of his musket; backside the richly attired helm, another guard accidently fires his musket, its smoke mixing with the white plume on the lieutenant's alpine hat (a comical near miss, and an actionable offence). Further to the right, a guard examines the barrel of his musket. Meanwhile, some figures, jostling backside the more prominent characters, are barely visible across a limb or, if y'all look very carefully, an middle and a partially glimpsed face. That eye to the upper left of Banning Cocq, belongs to the artist himself. Merely equally the Flemish artist Van Eyck loved to exercise, Rembrandt painted himself subconscious inside the scene.

And who is that brilliantly illuminated daughter dressed in gold and with a dead chicken tied to her waist? She is both of the scene and not. Rather than portraying a real person, she is a symbol or mascot, and the craven, or rather its prominent claws, is the emblem on the glaze of arms of Banning Cocq'southward company of Kloveniers (or Musketeers).

Just why a chicken and not an eagle, which surely would be more appropriate for a militia company, not to say more than dignified? At dignity's expense, Rembrandt appears to exist punning on the captain'due south name, fifty-fifty perhaps alluding to his appetites. What's more than, that mascot is surely the face of Rembrandt's Saskia?

And what of the guard accidentally firing his musket and nearly blasting the unsuspecting head off the lieutenant? We tin can't run into his face, merely his aboriginal helmet garlanded with oak leaves and his old-fashioned military attire. He too appears in the visitor and not of it. He also appears to allude to the company's history as something beyond that of civic pomp.

By painting a chicken and not an eagle, Rembrandt appears to be punning on the proper name of Banning Cocq (Credit: Rijksmuseum)

Though the figures of the helm and his lieutenant dazzle every bit the heads of their company, the guards must have seen Rembrandt's contemporaries paint far more formal militia portraits – stiffer, for sure, but above all, far more dignified than this. By the time Rembrandt painted Banning Cocq and his men, though the company's function had become largely ceremonial since peace had been forged with Espana decades before, there was clearly great pride in belonging to a civic militia.

Only hither Rembrandt's concerns are non bars to civic pride. Above all, he is interested in creating a drama and bringing information technology to life with emotional forcefulness, mixing a sense of the solemn (or at to the lowest degree of attempted solemnity) and the comic. Then here we take a ragtaggle crowd non quite managing to fall into step backside the figure of the captain as he gestures for his men to march out. Nobody had painted a militia painting quite like this before.

All the Rembrandts is an exhibition at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum commemorating 350 years since the creative person's death (Credit: Erik Smits, Rijksmuseum)

But contrary to the myth, which began early on in the 19th Century with influential biographies of the artist that chimed with the burgeoning thought of the creative person every bit outsider, Rembrandt continued to go commissions from the great and good.

Yet, ii factors greatly contributed to Rembrandt's problems in the 2nd half of the century. He was increasingly extravagant – the g house, the curios and antiques, the fine-art acquisitions. The other was to practise with his loose and crude handling of pigment. His style was going out of mode. What was coming in was the kind of highly polished 'fine painting' practised past the likes of Rembrandt's sometime pupil Gerrit Dou, who soon overshadowed his one-time master in terms of fame and success. Rembrandt had to await until the rise of the Impressionists before existence, in a sense, 'rediscovered' and placed in the story of art that drew a direct line from him to them.

Every bit for The Night Watch, it simply acquired that title in the 1790s, when the paint's varnish had darkened and was grimy plenty to suggest a crepuscular and mysterious night scene. Before then information technology was more prosaically known by the titles, The Militia Company of Commune Ii nether the Command of Captain Frans Banning Cocq, or The Shooting Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch. Still, even after being cleaned of that grimy varnish in 1946, the painting still manages to hold on to its mystery.

The Night Watch will be the centrepiece of the Rijksmuseum'due south All the Rembrandts from 15 February to 10 June before undergoing restoration from July. The restoration work volition take place before the public and will also be alive streamed.

If yous would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook folio or bulletin us onTwitter .

And if you liked this story, sign upwardly for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If Yous Just Read half-dozen Things This Week". A handpicked pick of stories from BBC Future, Civilization, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

0 Response to "Used Brass Restoration Hardware Tv Easle"

Post a Comment